About This Website

By trade, I am a writer, editor and photographer. On any given day, I may make my living doing any one of the three, but, right now, I am an editorial consultant to Beijing This Month Publications (BTMP) in Beijing, and all three skills come into play. At BTMP, since mid-2004, I have been involved in the English-language editing of Beijing This Month, Business Beijing and Art Beijing (new) magazines, the Beijing: The Magnificent City coffee-table photo album, the Beijing Official Guide, Beijing Investment Guide, the Map of Beijing. I have also been involved in major projects such as the VISION BEIJING photo and film projects, publishing projects in support of various governmental agencies in Beijing, Qingdao,Hangzhou and elsewhere, the first Beijing International Festival of Photography, various other photo projects and the New Beijing Great Olympics photographic exhibitions that have been held across China and around the world.

By trade, I am a writer, editor and photographer. On any given day, I may make my living doing any one of the three, but, right now, I am an editorial consultant to Beijing This Month Publications (BTMP) in Beijing, and all three skills come into play. At BTMP, since mid-2004, I have been involved in the English-language editing of Beijing This Month, Business Beijing and Art Beijing (new) magazines, the Beijing: The Magnificent City coffee-table photo album, the Beijing Official Guide, Beijing Investment Guide, the Map of Beijing. I have also been involved in major projects such as the VISION BEIJING photo and film projects, publishing projects in support of various governmental agencies in Beijing, Qingdao,Hangzhou and elsewhere, the first Beijing International Festival of Photography, various other photo projects and the New Beijing Great Olympics photographic exhibitions that have been held across China and around the world.

Update: In May 2014, my wife and I moved to Rockland, Maine, where we live and work.

I have been a soldier, serving with Co. C (Airborne), 172nd Infantry Brigade in Alaska (1966--67); Co. A, 2/504, 82nd Airborne Division in North Carolina; and in 1967--68 with Cos. B and E (Recon), 2/502, 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam. After the army experience, I attended the University of Texas at Arlington--BA, Communications (Journalism) 1974--and the University of Hawaii--MA, Asian Studies (China) 1977. Afterward, I worked in the oil and gas business and helped establish the Bin Ham Petrolane (now Bin Ham Petroline) coiled tubing service company in Abu Dhabi in 1983, before turning to jouralism in 1985. I worked for nearly ten years as a reporter for the Athens Daily Review in Athens, Texas, serving on the board of the Texas Outdoor Writers Association with great people like Charly McTee, Paul Hope, Larry Bozka, Sugar Ferris, Marty Malin, Larry Hodge, David Sams, Jim Foster, Bud McDonald and others. In Athens, I raised two fine sons, Preston and Dylan, the latter of which has given me three granddaughters.

In the 1990s, I began to long for the expatriate experience again; in 1998, after a brief stint with the Malakoff News, I found a copy editing job with China Daily in Beijing, where I began a completely new life at age 49. I returned to the United States with my wife Wang Nanfei (http:www.wangnanfei.com) in September 2000 so she could attend the University of North Texas, where she received her MFA in painting and sculpture in 2004. Afterwards, we returned to China where we joined by her mother and father Li Ge and Wang Guangsheng, two of the most interesting people I've ever known, in Beijing.

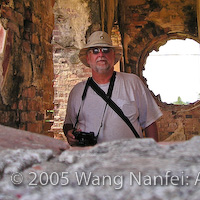

Photo: CJD at north portal of the Citadel, Hue, Vietnam (© 2005 Wang Nanfei)

This website exists to share my photographs and as an outlet for personal expression in images and words. The thoughts and ideas expressed are my own, unless otherwise stated. All the images and writings on www.charlesjdukes.com are copyrighted worldwide and may not be copied or used in any way without specific written permission.

This website exists to share my photographs and as an outlet for personal expression in images and words. The thoughts and ideas expressed are my own, unless otherwise stated. All the images and writings on www.charlesjdukes.com are copyrighted worldwide and may not be copied or used in any way without specific written permission.

I was interviewing the Vietnam veteran and Victor Six author David Christian once and made a remark that some things in the book didn't square with my own experience in Vietnam. David's response was calm but pointed: "Write your own book then." I've never found the time or had the inclination to write a book, but in recent years, the idea of creating a website has been percolating, and now I've gotten around to it.

I am a photographer, but this is not just a photographic website. And Images of Life includes more than photographic images: poetry, prose, commentary and whatever strikes my fancy are and will be included. You may even see some of my wife's work here from time to time. Later, I will create a portfolio of work I think people might want to buy and create a "store" that will allow them to do so.

My "private site" is a password-protected place I've set aside for photos of my family and friends around the world. Most of it would bore the average viewer, and I see no need to make this information public.

Blogging? We'll see...later.

Any comments or criticisms should be sent here: cjd@charlesjdukes.com.

I am smitten by photography. I cannot say I love it; it's too much trouble and demanding, but no matter what I do or how many bad pictures I take, I cannot escape it. It's like writing poetry; once you start, you cannot stop. It's a way of thinking that is vital to existence at times: at least for me.

As a child, I sometimes travelled with my father, who hauled bricks for Royall & Gatlin Sons trucking company and Texas Clay Products in Malakoff, Texas, and used the Voigtlander fold-out camera he brought home from Germany after his post-World War II service there to photograph the shipyards and drainage canals around Beaumont, Texas. These physical images and black and white negatives have been lost, but the images still come to mind.

Other cameras followed, from Kodak Brownies to the Polaroid Instamatic I sometimes used in Vietnam. I carried a Canon FTb to Australia in 1969, but after that I stopped using a camera and taking pictures for a time. I stopped because I felt it was interfering with my experience of things going on around me. After my time in Vietnam, about which I have very mixed feelings, I found that I wanted to live, not saying "No!" to anything going on around me, except for Nixon, the continuing war and racial conflict that I encountered upon my return. The late 1960s were an amazing, exhilarating and exciting time, but there was also great anger, disappointment and sadness: the time of Easy Rider. I travelled the country, trying to take in as much of it as I could, everything from race riots in Cairo, Illinois, to the Whiskey Go Go in LA, Bourbon Street in New Orleans and the beaches of Mazatlan.

I was majoring in philosophy when the war began to wind down; in 1971, I realized I needed to think about learning some kind of trade and preparing for life after college. There never have been a lot of jobs available to philosophers, especially the kind with my grade point average. I had taken up skydiving with Phil Mayfield of Irving, Texas, and suddenly found myself surrounded by photographically inclined people, like Richie Grimaldo of Dallas. So I turned to photography, traded in my Canon and got my first Nikon F, studying journalistic photography with Roy Hamric in the journalism department of the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) and under the late Hal McGuire, founder of Variety Photographic Industries, in Irving, Texas. Roy taught me how to write and take pictures for newspapers. Hal taught me black and white photography and let me use his huge Nord color processor. Doyle Shields of El Camino Cameras in Irving, Texas, discussed photography for hours on end, and he extended credit when I had a job to do and needed paper, developer or other expendables.

In 1972, I took a break from school following a divorce and travelled to Elsinore, California, where I took skydiving stills and shot 16mm film for my friend Joe Garcia. There, I was inspired by Carl Boenish, Ray Cottingham and Chip Maury, the latter a US Navy journalist, all greats of skydiving photography. Maury, in particular, reawakened an interest in journalism. Skydiving then took me to Venezuela. When I returned from Venezuela in 1973, I learned UTA had started a journalism program; so I switched my major to journalism. Photography and learning how to cook Thai food from my friend Chumpon Buranaphan helped make my last year at UTA a good one.

Though I took photos all the while, snapshots really, it would be nearly 11 years before I'd take up a camera for work, mostly in support of my writing for newspapers and magazines. Sadly, all along the way, I found it very difficult to sell photos and to improve my skills, especially when living in a rural area in East Texas. The deeper I got into magazine writing, the less time I had to manage the photography side of things, especially slide management. Gear and photo-book expenses were outrageous. So I just shot in support of my own work using Nikon FM2s and later a Nikon F4, the F4 I took to China, where I shot far too little between 1998 and late 2000.

Aside for some remunerative schlock work for lawyers in Houston in 2002, photography took a back seat to assisting my wife in her MFA, studying html, Photoshop, PageMaker and finally Dreamweaver MX before our return to China in 2004 and working with the sculptor James Surls. I knew that whatever I did as a journalist in the future, on any level, would involve digitalization. I was fascinated with the quality of the images taken by my wife's little Olympus D-560 digital camera.

After my return to China, photo expenses continued to be a huge burden, both in terms of monetary expense and the time spent travelling to and from the processors (much of a working day in some cases). The management problem reared its ugly head again: they don't mount slides at the processor for you in Beijing. For a long time, the best way to store pictures was to leave them in the sleeves that came from the processors. Over the past several years, this situation has begun to change, and I recently found a supplier for PrintFile products, but pro services are still just getting off the ground.

This turned me to digital. I took the plunge with a Panasonic DMC-LC1. I liked its Leica-like look and the quality of the photos it took, although, frankly, I still liked the Olympus's images better straight from the camera. Soon enough, however, the limitations of the DMC-LC1 would become obvious; it was very slow, and with the failure of the rear dial mechanism and constantly sticking shutter button, it became undependable. I found myself constantly trying to get the zoom lens to go wider.

Then, we moved our BTMP editorial offices back to a building on Fahuananli in Chongwen District in Beijing, just off Xingfu Dajie and Wenzhang Hutong (hutong means lane in Mandarin Chinese). Two things happened: I learned that the low houses (pingfang) across the street from our office that lined dozens of narrow hutong, where I loved to wander before and after work and during lunch, were to be demolished, and our organization began organizing a lot of photo events, some involving top-grade pros like Joe McNally, Gideon Mendel, Harry Mattison, Yann Layma, Gilles Sabrie, Kenneth Jarecke and more.

It was like a shot to the brain being exposed to some of these pros: I realized the only thing stopping me from doing the kind of work I wanted to do was none other than ME! I began looking for something I could do, that I could get access to and that I'd have time to do properly (time on task). After some thought, I assigned myself to cover the changes in and the probable demise of the old neighborhood that I viewed outside my office window every day. I have thrown myself into what I call my Wenzhang Hutong Project.

Delving deeper into the project, I bought a Nikon D200 and several DX lenses to join the 1990s vintage Nikkor lenses I already had. Then the Nikon D3 came along, and I just had to have it: the project deserved it, and it was perfect for the project. The D3 is just a tool, to be sure, but it's one of those tools that you admire regardless of its function. It does what I want it to do; it does it well and it's tough. More than 100,000 images later (shooting RAW+Jpeg) it just keeps working.

Update: Now I shoot in RAW only, and I've added a Nikon D800 to my kit.

Then came the needed software, then an iMac to run the software, then updates to the software. Complexity has piled upon complexity, expense on expense and the learning curves have been steep. After spending far too much of my time in Internet bars in Chiang Mai copying files on junk computers during a vacation in 2005, I resolved never to travel without a laptop again; so I am now the very proud owner of a 13" MacBook Pro with 8 GB ram and Firewire 800. Another great set of tools.

Ironically, the learning curve has not only sent me back in the direction of film, but toward 4X5 and 8X10 work for the first time. Beautiful Chinese-made Chamonix 4X5 and 8X10 field cameras have been added to the arsenal, and I'm trying to learn how to use them and incorporate them into my life, work and various projects.

This website is just another part of the deal.

Photo: A girl and her teacher in a hutong (©2009 Charles J. Dukes: All Rights Reserved)

I've used Nikon cameras almost exclusively since 1971. During that time, only two have failed, the film advance on an FM2 that I too exhuberantly wound while covering a drug raid and the shutter on my F4 that failed after eight years of service, which was repaired. The camera still functions today. I started with digital using a borrowed Olympus D-560 point and shoot and the entry-level Panasonic DMC-LC1 before I tired of its sticky shutter release and got a Nikon D200. I got the Nikon D3 because of its fast and easy handling, good shutter release and the ability to make good large prints for exhibitons such as the group show I'll be in with my wife starting April 7, 2011, at the Colorado University Museum of Art (CU Museum of Art) in Boulder. On the film side, I still have a Nikon FM2 (recently repaired and in great operating order), a Nikon F4 and the excellent Zhejiang, China-made Chamonix 4X5.

I've used Nikon cameras almost exclusively since 1971. During that time, only two have failed, the film advance on an FM2 that I too exhuberantly wound while covering a drug raid and the shutter on my F4 that failed after eight years of service, which was repaired. The camera still functions today. I started with digital using a borrowed Olympus D-560 point and shoot and the entry-level Panasonic DMC-LC1 before I tired of its sticky shutter release and got a Nikon D200. I got the Nikon D3 because of its fast and easy handling, good shutter release and the ability to make good large prints for exhibitons such as the group show I'll be in with my wife starting April 7, 2011, at the Colorado University Museum of Art (CU Museum of Art) in Boulder. On the film side, I still have a Nikon FM2 (recently repaired and in great operating order), a Nikon F4 and the excellent Zhejiang, China-made Chamonix 4X5.

Update: I added a Nikon D800 and Chamonix 8X10 to my arsenal before leaving China.

I was using a Nikon LS-2000 film scanner, but it died. I recently replaced an Epson 3200 flat-bed scanner I left in Texas in 2004 with an Epson Perfection V750 Pro. So far, I'm very happy with it, but again, I have far too little time to use it and doubt I'll ever master it. I'm using Adobe Lightroom 3 (latest release) to organize and process my photos and web galleries, along with Photoshop CS4, Nikon's Capture NX2 with Nik Efex 3.0 and DxO Optics Pro, and now the Nik collection of Lightroom plug-ins.

The biggest issue with gear in China is packing light. Unless you use private transporation in China, carry less than you can carry. If you ever get stuck in a huge crowd on a subway or an event, you will immediately understand what I'm talking about if you're carrying more than a camera and a couple of lenses. Large bags on rollers? Forget it. A South China Morning Post photographer I travelled with once carried a wide zoom and mid-range zoom, one on his Canon and the other in a non-descript waist pouch that he wore to his front on the street, and that is all.

Photo: Charles J. Dukes carrying too much gear and too much gut at an orchid garden in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008 (©2008 Wang Nanfei: All Rights Reserved)

This site is under construction and will be for some time. I can be said that there's a lot of "sub-par" images here, to which I answer: "Guilty as charged!" This is not a "portfolio," as my LZ White photos on the Vietnam pages will attest. Most of those were taken by my wife with a point and shoot camera, but there is a story there, and that story, as well, will be fleshed out in time with copies of newspapers and so forth. So this website is a long-term project. [Update: After the global financial crisis of 2007 and its deepening in China in 2009, my workload in China got much heavier and more difficult, so bad that I decided to leave Beijing in 2014. During this time, I had almost no time for a personal life, much less to work on the website. I expect to change this reality in 2015, beginning now.] The pressures of a day job have been intense in 2011 and it takes about two days of steady work to prepare a Lightroom 3 web gallery, write captions, load it, work out the bugs so you can see what's available as things are without any grief. Sometimes I overdo the editing and can't get right back to the image to clean it up, but I have dismissed "doing nothing" as an option. I'm ready to take my licks. Hopefully, I'll be able to constantly improve it, which is my goal.

This site is under construction and will be for some time. I can be said that there's a lot of "sub-par" images here, to which I answer: "Guilty as charged!" This is not a "portfolio," as my LZ White photos on the Vietnam pages will attest. Most of those were taken by my wife with a point and shoot camera, but there is a story there, and that story, as well, will be fleshed out in time with copies of newspapers and so forth. So this website is a long-term project. [Update: After the global financial crisis of 2007 and its deepening in China in 2009, my workload in China got much heavier and more difficult, so bad that I decided to leave Beijing in 2014. During this time, I had almost no time for a personal life, much less to work on the website. I expect to change this reality in 2015, beginning now.] The pressures of a day job have been intense in 2011 and it takes about two days of steady work to prepare a Lightroom 3 web gallery, write captions, load it, work out the bugs so you can see what's available as things are without any grief. Sometimes I overdo the editing and can't get right back to the image to clean it up, but I have dismissed "doing nothing" as an option. I'm ready to take my licks. Hopefully, I'll be able to constantly improve it, which is my goal.

With the 2011 tourist season upon us, I had planned to write some things about taking photos in China, but, again, time was short. Suffice to say that with minor exceptions, taking photos in China is a breeze. If you're using a digital camera and you take a shot, show curious people that you treated them with dignity and they won't mind, although some will feign embarassment and some will actually be embarassed that you thought they or their village or street were beautiful enough to shoot. But, mostly, people who are used to and comfortable in their surroundings will most likely wonder what you see that you think is worth taking a picture of; often they'll look in the direction of the shot, back at you then back in the direction of the shot before they continue their walk, uttering "laowai" and shaking their heads.

Exceptions include foreigners in bar street areas and Chinese street vendors who are mostly operating illegally, especially in the big cities. Among these, the quack dentists and drug salesmen and for some reason guys who sharpen knives on the streets and in neighbourhoods are most likely to object. Stay clear of drunks. Some busybodies in some neighbourhoods will ask why you're taking images of old people and old buildings and will ask why you don't go take photos of more modern stuff they're prouder of. Try to visit with these people if you can: show them the beautiful pictures you took and they'll relax and even help sometimes. All of these people sometimes have tough lives and don't trust a lot of people in the city, whether Chinese or foreigners. So be sensitive; no picture is worth creating an "international incident" or getting into a tussle, especially if it involves the police.

I was detained by a young policeman once in a small town in Shandong Province called Yanzhou, about ten kilometres from Qufu, the home and resting place of Confucius, but that was in 1998. I was taking pictures of some elderly tangerine vendors who were preparing a bag of tangerines for me. The policeman had never dealt with a foreigner before and he detained me. Fortunately for me, I'd met the police chief there in a restaurant the day before, and he came and sorted it out, but it was through this incident that I learned that one of the most important standing orders of a policeman or soldier in China is to protect the elderly from embarassment or even potential embarassment. The young officer was just doing his job; he reported he'd been following me, and all I took photos of was old things, which to him meant I was planning to embarass China or at least Yanzhou. On the other hand, he could hardly believe that an American worked for a Chinese newspaper in Beijing, as I'd told him, even showing him my China Daily ID card. A woman who spoke English in the crowd said, "He doesn't believe you." But these kinds of things seldom happen any more, except for hard charging news guys in controversial situations.

China is not only opening, but opening to tourists and new tourism committees have been formed at all levels to ensure that all departments in the government know how to keep tourists happy. Still, don't abuse the privilege of being in China; this is still a fairly conservative society. Using commonsense will get you by most of the time, but remember: the western sense of common sense and the Chinese sense of commonsense are sometimes wildly at odds. If you do get in a jam, be patient, don't get angry, don't yell and most of all, don't strike out. Usually, someone in the crowd will come to your aid.

If someone really bothers you in public when taking photos, tell them: "Call the police." This is something that will usually calm a situation, because few people on the street want to have any problem with the police, especially in an argument with a foreigner, but this only works if you are 100 percent in the right. Maybe you're not; so be sensitive.

Lastly, for now, it's hard to say this too often: pack light and don't carry more than you can carry, unless you can afford to hire someone to carry and watch after your gear. You will appreciate this wisdom anywhere in Asia if you find you need to take a bus or ride a subway during rush hours.

Photo: Woman in Yeri, Diebu County, Gannan, Gansu Province in October 2010 (©2010 Charles J. Dukes: All Rights Reserved)

Other: Large Format in China

As of 2014, with China's increasing prosperity, many people had begun experimenting with "old" things, whether clothes, toys, electronic gadgets, antiques and collectibles, vinyl records and phonographs.... In some ways, it seemed an effort to catch up on what they'd missed out on in the past. This is especially true in the the field of photography. It appeared that film was dying out in about 2000 or so as digital photography came on the scene, but by 2004 several of my Chinese friends had begun experimenting with pinhole cameras. Also, people began to start buying old Seagull and other Chinese, Russian and East German small and medium format cameras. Still later, a mountain climber in Zhejiang Province began producing the Chamonix large-format camera line that caught the attention of large-format fans worldwide. By 2014, when I left China after ten years, people were using every kind of camera you could imagine, from 20X24 large format cameras, to Mamiya 6X7s, Lomography, pinhole cameras and everything in between.

When I got to China first in 1998, it was odd to see ordinary Chinese with any kind of camera; there were almost no cellular phones, only "beepeejees" (beepers). By the summer of 2014, it was not unusual to see every kind of Nikon or Canon imaginable, and with long f2.8 telephoto lenses hanging from them.

In addition, artists and others had begun experimenting with all kinds of photographic processes, such as platinum and wet-plate printing and all kinds of transfer processes.

Of course, smart phones are ubiquitous, and finding someone in a Chinese crowd without a camera phone would be unusual these days outside the poorest rural areas in the country.

Still, for many people, large format cameras are an oddity, so if you try to use one in China, expect to draw a crowd, unless you're in a very remote place.

I was trying to photography bridges at Kunming Lake at the Summer Palace once and I knew I had to pick a proper place to shoot, not just the best place, to keep from getting trampled by a weekend crowd. I picked a place along a wall where the path narrowed to a point at another high wall; it was impossible to go further. I figured this would give me enough protection to shoot.

As I prepared to take my shot, I turned and grabbed my dark cloth, and looking at my ground glass, I snuggled the cloth around the camera. But I couldn't see anything except darkness with light around the edges. I couldn't figure out why, so I reached around to make sure I'd removed the lens cover. It was gone. So I wondered if I'd left the rear lens cover partially on or something. So undid my dark cloth and looked up to see a guy hanging from the lakeside wall with his eye pressed against my lens, trying to look back at me! In addition, people were going through my camera bag, fiddling with spare lenses and the like, and when I looked up, they began asking me what all this stuff was. I didn't know whether to get pissed or laugh, so I laughed and explained that what they were looking at was a camera and lenses from another time.

They were amused, but I was sure they were wondering why I was dragging all that stuff around in the rain when a cell phone would do just fine.

Another day in China.